|

|

|

|

|

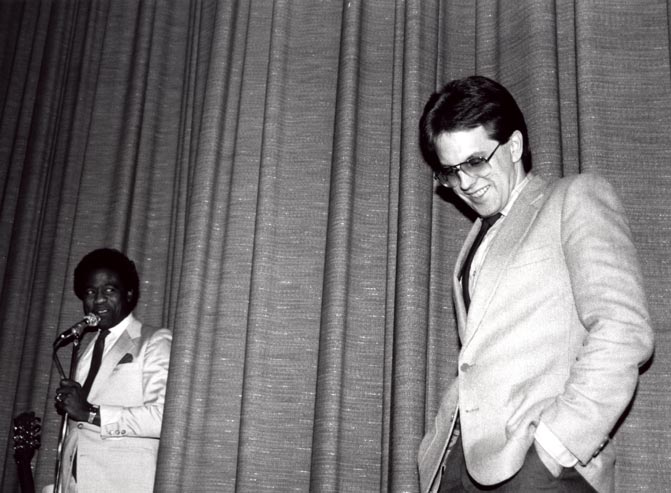

Al Green and Robert Mugge at the October 25, 1985 American theatrical premiere of

GOSPEL ACCORDING TO AL GREEN

at the Coolidge Corner in Brookline, MA. Photo by Justin Freed. |

| |

|

| |

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL |

February 21-22, 2009

Two '80s Film Flashbacks

Sonny Rollins and Al Green Documentaries, New on DVD

By Will Friedwald

When Robert Mugge's documentaries "Sonny Rollins Saxophone

Colossus" (1986) and "Gospel According to Al Green" (1984)

were made, they were intended as a permanent record of two seminal

musicians at a very specific point in their careers. The central

figures themselves had axes to grind: Sonny Rollins -- and even

more so, his manager and wife, Lucille -- wanted to silence the

critics and fans who insisted that his contemporary work was inferior

to his classic albums of the '50s and '60s; Al Green was compelled

to explain to the world why he gave up singing pop music and devoted

his life to spreading God's word.

Today, those particular points don't matter as much as they once

did. Mr. Rollins is treated as a living legend, whose every performance,

young and old, is rightfully cherished; Mr. Green himself made

another career change and since the mid-1990s has been performing

secular as well as sacred music, knowing full well that audiences

will accept him no matter what he sings.

But these two films, newly released on DVD by Acorn Media, hold

up well as vital profiles of their subjects at turning points in

their lives, each combining a concert film with a journalistic

backstory. They also remind us how much the genre has changed in

the past two decades, a period of ever-shortening attention spans.

When Mr. Mugge made these documentaries (both of which exceed 1½ hours

in length, with not a minute wasted), it didn't seem like too much

to ask an audience to watch a man play a sax for 10 minutes straight.

"Saxophone Colossus," which takes its title from Mr.

Rollins's celebrated 1956 album, begins with the musician talking

about how he prepares for a performance; although it isn't exactly

through "meditating," he does drop that word, and both

of Mr. Mugge's films are extended meditations on one man's contributions

to music.

The filmmaker and his camera crew capture Mr. Rollins in performance

at two events. At the first, he and the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony

Orchestra play the "Concerto for Tenor Saxophone and Orchestra," Mr.

Rollins's collaboration with the Finnish arranger-composer-conductor

Heikki Saramanto. In the accompanying commentary, the director

explains that he thought the work might become a jazz classic on

the level of John Coltrane's suite "A Love Supreme." Instead,

the concerto -- though it's a fascinating piece, which includes

one movement that sounds inspired by Aaron Copland and another

by Caribbean music -- sank into obscurity. It has never been issued

on CD.

The other concert included in "Saxophone Colossus" is

an August 1986 date in a rock quarry converted into a performance

space. Mr. Mugge's intention was to show the high level at which

Mr. Rollins performs even at a bread-and-butter gig with his regular

working band (including trombonist Clifton Anderson and bassist

Bob Cranshaw, who are still with him today).

Less than a half hour in, Mr. Rollins plays a short, unaccompanied

medley of several themes, including "A Kiss to Build a Dream

On" and "How Are Things in Glocca Morra," and then

jumps off the stage. Apparently, he was frustrated by the sound

of his tenor sax -- which had changed since it was relacquered.

He was intending to head into the outdoor audience, and to play

among them like a strolling musician. He hits the ground with such

force that his heel bone snaps, and he lies down on the stone,

flat on his back. Then, still horizontal, he begins to play "Autumn

Nocturne," with neither the audience nor the band realizing

that a bone is actually broken in his foot. In the days before

tiny video cameras and cellphone photography, this was an extraordinary

slice of reality to capture on film.

* * *

"Gospel According to Al Green" is driven by the irresistible,

almost aggressive charisma of its central figure (who won two more

Grammy Awards earlier this month). Not only does the Rev. Al Green

exude the same energy when singing of love for a woman or love

for Jesus, but he acknowledges no difference between preaching

in a Baptist church, addressing an audience in a night club, or

being interviewed by Mr. Mugge in a recording studio. Whether a

camera crew or a crowd of thousands is listening to him, he speaks

as if he's talking to his most intimate friend.

His recounting of hearing the word from God that he must be born

again is compelling enough to make even a nonbeliever get down

on his knees. The story of how a vengeful ex-lover attacked him

by throwing a cauldron of boiling hot grits on him, and then shot

herself, is by turns both comic and tragic. There's a touching

moment when his once and future producer, Willie Mitchell, tells

of how their partnership ended when Mr. Green stopped singing pop

songs. It is ironically underscored by their 1972 hit "Let's

Stay Together."

But "Gospel According to Al Green," like "Saxophone

Colossus," is ultimately driven by the music, which we get

to hear at its proper length. Mr. Green describes gospel music

as having "an electricity that's got nothin' to do with sex," but

there's an overt sensuality to his performance here -- whether

describing romantic or spiritual ecstasy. He makes it clear that

both come from the same place in the heart.

Mr. Friedwald writes about jazz and other music for the Journal.

Reprinted from The

Wall Street Journal © 2009 Dow Jones & Company. All

rights reserved. |

| |

| |

THE MEMPHIS FLYER |

February 26, 2009

Full of Fire

A classic documentary captures Al

Green in the pulpit and onstage.

By Chris Herrington

The first time I interviewed Al Green, on the phone, several years

ago, the legendary soul singer took me by surprise. I'd been a

huge fan of his music for years, but not only had I never spoken

to him, I had never seen or heard him interviewed.

Green's speaking manner was nearly as idiosyncratic and dynamic

as his one-of-a-kind vocals. Not only was his normal conversation

sing-songy, he would break, literally, into song. Asking a question

about his music's connection to Motown, Green burst into Temptations

and Smokey Robinson songs. Throughout the interview, when songs

were mentioned, he would occasionally dip into them, weaving bits

of singing in and out of the conversation.

Had I seen filmmaker Robert Mugge's 1984 documentary Gospel

According to Al Green, I might have been better prepared. In that film, Green

is first seen in his home studio, being interviewed while plucking

an electric guitar. "I love you with all my heart," he

sings, picking out a few notes and making the cliché soar.

A few minutes later, Green tells the story of playing a show in

Dallas, early in his career, and not getting paid. Driving back

home to Michigan, a girlfriend with him, he sings a new song he'd

written, "Tired of Being Along." Strumming the guitar

the whole time, Green interrupts his own story periodically to

sing the song's opening verse or chorus.

"The girl said, 'Would you please put that thing down? You're

driving me nuts,'" Green remembers with a grin. "But

I was gone on that song."

Green's way of speaking is almost fey — downright cutesy — as

stylized as his singing. In the mid-'70s, critic Robert Christgau — a

big fan — wrote of Green's speech: "The man crinkles

up his voice as if he's trying out for Sesame Street; he drawls

like someone affecting a drawl; he hesitates and giggles and murmurs

and swallows his words."

Green is having a very good year. His 2008 album Lay It Down,

was the best of a fine trio of recent secular "comeback" albums.

A few weeks ago, the album garnered Green two Grammys on a night

where he dueted with fellow Mid-Southerner Justin Timberlake on

his classic single "Let's Stay Together."

Soon after Green's big Grammy moment, the long-unavailable Gospel

According to Al Green received a 25th-anniversary DVD release,

allowing viewers a remarkably intimate glimpse of Green in the

days not long after he'd essentially abandoned secular music for

the pulpit.

Mugge is a documentarian who specializes in making films about

American music, including such high-profile works as Deep Blues, Saxophone Colossus (a film about jazz great Sonny Rollins re-released

concurrently with Gospel According to Al Green), and the post-Katrina

New Orleans Music in Exile. Gospel According to Al Green was one

of Mugge's first films, but the director apparently sees it as

a template for his subsequent work. In a new interview that is

one of the new edition's special features, Mugge says, "In

many respects, Gospel According to Al Green is exactly what I want

my films to be: It captures a musical artist at the peak of his

powers; it develops many themes related to traditional American

music; and it presents a dramatic story."

That story is part of pop-music lore: how Green, a journeyman

Michigan soul singer with Southern roots, was discovered by Memphis

producer Willie Mitchell at a Texas club and lured to Tennessee;

how Green and Mitchell worked to perfect a soul sound that bridged

the divide between '60s grit and '70s silk; the dramatic incident

where Green was scalded with hot grits by an upset lover, who then

killed herself; how Green had a religious awakening, abandoning

pop music for the pulpit in the form of his own Memphis church:

the Full Gospel Tabernacle on Hale Road.

This story has never been told with such intimacy as in Gospel

According to Al Green. Green was candid on these subjects in his

2000 autobiography Take Me to the River, but here you hear the

words in Green's amazing voice and you can watch, rapt no doubt,

as he performs his life story with the same charisma as he performs

his great songs.

Gospel According to Al Green captures its subject in three primary

settings: alone in his home studio, onstage at Bolling Air Force

Base in Washington, D.C., and, finally, in the pulpit at Full Gospel

Tabernacle. The only other subjects who get much screen time are

Willie Mitchell, interviewed at Royal Studio, where most of Green's

greatest work was recorded, and the pop critic Ken Tucker, who

calls Green a synthesis or the soft, wounded style of Smokey Robinson

and grit of Wilson Pickett.

Originally, Mugge says in his DVD extra interview, there were

other outside talking heads in the film and the director had included

himself as an on-screen subject. That material didn't test well

in early screenings: The audience just wanted to watch Green talking,

singing, and preaching — performances all.

At Bolling, Green stretches out Curtis Mayfield's "People

Get Ready" and goes deep into the gospel standard "Nearer

My God to Thee" while walking off the stage and into the crowd.

In the studio, he's riveting, talking candidly about the "grits" incident

and his middle-of-the-night religious awakening. Most memorable

is his description of his impulsive purchase of his church.

"You know how I wrote the check?" Green asks, reaching

into the breast pocket of his suit and pulling out his glasses. "Out

of a little book I had in my pocket. Just a little pad book. Not

even a real, real, real book. Just a little pad book.

"I wrote the check right on out for the whole building," Green

says, running his fingers over his glasses as if they were the

checkbook. "And signed it," he says, waving his hand

dismissively. "Through with that. 'Cause see, now, Sunday

I'm preaching. That's all."

Mugge holds back on Green's church service until the final third

of the film, when he surprisingly gives Green in the pulpit roughly

half an hour of uncommented-on screen time, where you notice how

little difference there is between Green's three public sides:

speaking, singing, and preaching. Green is, here, improvisational,

his voicing ranging between speech and song.

"This is a film about love," Mugge says. "About

the connections between soul music and gospel, and about a guy

who flew too close to the sun, got his eyeballs burned, and has

been singing ever since with fire coming out of his mouth."

And to borrow a title of one of Green's many terrific '70s albums,

he's nothing if not full of fire here.

Reprinted with permission from The Memphis Flyer |

| |

| |

| |

| |

THE CITY PAPER (Nashville) |

February 3, 2009

OnDVD: New releases spotlight Green, Rollins

By

Ron Wynn

Acclaimed director Robert

Mugge has excelled as a music documentarian over the past three

decades. His productions have profiled both famous and obscure

performers in numerous genres. The long list of exceptional Mugge

productions include a pair of 1980s works on Al Green and Sonny

Rollins that have just been reissued on DVD.

Gospel According to Al Green and Sonny Rollins:

Saxophone Colossus (both Acorn Media) represent the finest filmed presentations

ever done on these two giants of American music, and each blend

insights and splendid, rare performance footage in a manner that

distinguishes them from basic concert or documentary items.

Al Green had made the transition from soul matinee idol to hard-working

minister by 1984, the year Mugge originally filmed Gospel

According to Al Green. He talks extensively about the events that led to

his abandoning that soul career, and also discusses the problems

he experienced in establishing and maintaining his Memphis church.

For those skeptical about Green’s conversion, the DVD

includes a marvelous example pastor Green, as he presents a rich

sermon that combines biblical references, personal stories and

occasional song inserts. The package also has several scenes

from his church services, which sometimes extend for hours on

Sunday mornings and afternoons.

But the DVD also showcases the masterful Green secular style,

with excerpts from performances featuring magnificent renditions

of classic hits like “Let’s Stay Together” as

well as equally strong gospel numbers such as “Amazing

Grace.”

Green addresses the demands of both stardom and the ministry

with equal fervor, explaining that each demands an intensity

and commitment that can be draining and debilitating.

Through a nearly 90-minute interview, viewers see sides of Green

he’s never before or since revealed. The set is completed

with the inclusion of the original theatrical trailer and Mugge’s

reflections on the project.

As for Sonny Rollins, he began playing the saxophone as an 11-year-old

and was working with Thelonious Monk before he was 18. His soaring,

relentless solos and integrity as a performer have made him a

beloved figure.

Rollins also has often walked away from the music scene when

he felt his playing was getting stale or predictable, even at

times when his work was extremely popular. Sonny Rollins:

Saxophone Colossus was filmed in 1986, only a year after he’d started

recording and performing again following almost nine years out

of the spotlight.

His DVD includes far more comments and conversation from Rollins

(who’s never sought the spotlight) about his background

and interests than usual. He goes into very specific detail about

the importance of spirituality in his life and music, while dissecting

his approach to improvisation and performance.

A song’s melody has always been what has most attracted

Rollins to a composition, and his ability to hear alternative

directions in a tune while exploring it and his experiments with

song structure are displayed in wonderful footage of him teaming

with a Japanese symphony orchestra in Tokyo and a smaller group

in New York.

While not extensively or exclusively a concert film, Sonny

Rollins: Saxophone Colossus amply examines the Rollins musical method,

while also giving fans vital insight into his interests and life

away from the bandstand.

Reprinted with permission from The

City Paper - Nashville's Online Source for Daily News |

| |

| |

THE ALL MOVIE GUIDE |

December 24, 2008

Gospel

According to Al Green and Saxophone Colossus: The All Movie

Guide Review

By Nathan Southern

This January will witness a very special event – the

DVD reissue of two of the most brilliant music documentaries

of the past quarter century, both by the gifted Robert

Mugge: 1984’s Gospel

According to Al Green, and 1986’s Sonny Rollins: Saxophone

Colossus. Acorn Media is handling the rereleases, with a number

of supplements including directorial reflections by Mugge; these

welcome additions do enrich the films, but more prominent is

the supreme craftsmanship of both works themselves. I took a

fresh look at these two modern classics over the weekend and

felt particularly struck by how well they succeed in completely

different arenas and with completely distinct voices – a

testament to Mugge’s versatility and adaptability as a

craftsperson.

Shot at the tail end of 1983, Gospel According

to Al Green went into production about a decade after Green’s

famous conversion to Pentecostalism, and six years after his purchase

of the Full Gospel Tabernacle Church in Memphis and his temporary

refusal to perform any of his soulful R&B hits again. Mugge

intercuts several elements within the film: a shockingly candid

and revelatory interview with Green, an impromptu recording session

of the chart-topper “Let’s Stay Together” (with

Green agreeing to set aside his secular music ban for the sake

of Mugge’s cameras), a concert by Green at the Bolling Air

Force Base and Noncommissioned Officer’s Club in honor of

1984 Black History Week, and a sermon at Green’s church.

Especially

in its early stages, the documentary pulls its power from Green’s almost hypnotic and mesmeric music, which

exerts an astonishing level of emotional pull toward the onscreen

and offscreen audiences; few cinematic outings have captured

this aspect of gospel music so beautifully. (Compare the film,

for example, to other gospel documentaries that interrupt the

flow and emotional throes of the music with frequent cutaways).

Mugge avoids that error by courageously letting the audience

observe the concert portions for extended periods of time (thus

wisely trusting in his subject matter) and allowing the music

to build, to such a degree that its overall emotional structure

begins to mirror the emotional structure of one of Green’s

Willie Mitchell-produced songs as described in an onscreen interview

with Mitchell – a gradual build to crescendo: “I

think a song should be like climbing a mountain… Start

at the bottom and climb to the top.” Mugge employs a like

narrative structure in the documentary itself.

Via the interviews

with Green, Mugge also provides intimate observations of a fascinating

character – it’s possible

that we’ve never before witnessed an interview subject

so animated by torrents of histrionic emotion – to such

a degree that it pushes Green beyond the point of eccentricity,

and makes him a source of endless curiosity. The film doesn’t

shy away from the possibility that Green enjoys being a spectacle

in and of himself, and Mugge, in fact, places his camera at exactly

the right places to observe the contradictions of this superstar,

who on the one hand projects very sincere devotion to his audiences

and a very sincere belief in Christian music and the Christian

gospel, and on the other hand grows visibly disinterested on

those brief occasions when someone else takes center stage. Meanwhile,

the film’s interview portions enable Green’s fascinating

personal story to emerge and build, and the documentary achieves

greatest profundity by establishing a link between the notorious

crisis that pushed the singer to the edge (when a distraught

girlfriend dumped boiling hot grits on him in the shower, then

shot herself) and the reliance on a spiritual anchor as a coping

device. Mugge ingeniously juxtaposes Green’s recollections

of the “incident” with a concert performance of “Amazing

Grace” featuring cathartic monologues that witness Green

openly dealing, before an audience, with the tumult that befell

him years earlier. More broadly, the film serves as a profound

reflection on the link, historically, between secular soul music

and African-American gospel music, and the extent to which the

former is often used as a tool to enervate and shape the latter.

Sans commentary, the film probes this intra-genre area gracefully,

yet wordlessly.

Above all else, the film witnesses one of the

greatest of all soul singers at the peak of his abilities and

provides marvelous entertainment.

That can also be said of 1986’s Sonny

Rollins: Saxophone Colossus, though the emotional texture

and narrative structure of this opus stand alone. Hard bop

tenor saxophonist Rollins,

regarded by many as the world’s greatest jazz improviser,

made history by adapting the jazz stylings of Charlie Parker

to his chosen instrument, but by the mid-late 1980s, Rollins’s

wife-turned-manager, Lucille, felt concerned that his star

might be fading, despite the fact that he was performing more

brilliantly, at that point in his life, than at any other time.

Mugge’s film was thus designed as a vehicle to reassert

Rollins’s greatness, and on that level alone it succeeds

wonderfully. The writer-director divides the bulk of the film

between four elements: candid interviews with Rollins and his

wife, an August 1986 performance with a small jazz ensemble

headlined by Rollins at Saugarties New York’s Opus 40,

a series of reflections on Rollins by jazz critics Ira Gitler,

Gary Giddins and Francis Davis, and – as the centerpiece – the

only official filmed record of Rollins’s Concerto for

Tenor Saxophone and Orchestra, Movements 1, 3, 4, 5 and 7,

mounted and performed in Japan in May of ’86.

Rollins, like

Green, is fascinating to watch, and though he’s

as complex a subject as one can imagine, we never feel the sense

of any emotional turmoil surrounding the musician that we do

from Green – only open, free, and unbridled joy that extends

to the film itself. (Just witness, for example, Sonny’s

rapturous performance of “Don’t Stop the Carnival” at

the Opus 40 that wraps the film). Structurally, Mugge approaches

Rollins as a subject by using the various interview and concert

materials to create a kind of interwoven narrative tapestry,

that builds to an impressionistic portrait of the musician. By

the time that the final sequence rolls around, we’ve gained

a myriad of insights into this legendary musician yet sense that

there are still many mysteries about him to be uncovered – the

film succeeds in building our curiosity and fascination. Musically,

the very best that can be said about Saxophone Colossus is that

a myriad of melodic complexities play out onscreen (including

the Japanese sequence – a groundbreaking fusion of fixed

symphonic structures and free jazz saxophone riffs), but one

can approach the material with only the most rudimentary knowledge

of what jazz improvisation entails, and actually learn the fundamentals

from watching Sonny’s performance. Mugge seems intent on

repeatedly filming Rollins from low angles, to enforce the musician’s

stature as a jazz giant (which partially explains the title);

with another subject, that might seem cliched, but the filmmaker

understands that the level of performance on display in the film

and the visual approach can do nothing but validate one another.

Reprinted with permission from the All

Movie Blog |

|

|

|