|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

Quest for knowledge, adventure drives filmmaker Bob Mugge

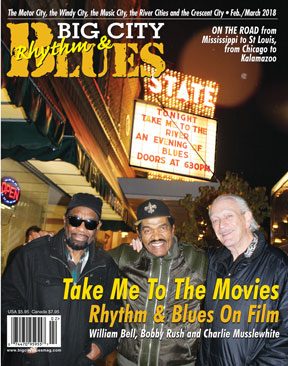

MUNCIE -- Early in his film-making career, Bob Mugge was writing screenplays and scrambling to raise money to turn those scripts into feature films. In his spare time? "I was making fun little music films on the side," he said. The thing was, he came to notice that his feature films never got funded, but those "little music films" always did. "I quickly became typed as making music docs," he said, referring to documentaries. Today, the Chicago native who grew up in Silver Spring, Md., is a youngish-looking 61 years old and teaching at Ball State University, where since 2009 he has filled the Edmund F. and Virginia B. Ball Chair in Telecommunications. He also has a list of film credits about as long as your arm. Some feature bluegrass or jazz or totally non-music subjects, but many others center on the blues. The Return of Ruben Blades. Gospel According to Al Green. All Jams on Deck. Big Shoes. Lookin' for Trouble. Last of the Mississippi Jukes. Hellhounds on My Trail: The Afterlife of Robert Johnson. These are just some of the 30 or so films Mugge (pronounced "muggy") has made. They have earned him high praise from publications including The Village Voice and The New York Times, with Frank Scheck of The Hollywood Reporter writing "Mugge has, during the past 25 years, established himself as the cinema's foremost music documentarian ..." The product of an experimental high school who at one point managed a combination head shop/coffee house, his artistic interests in college days included poetry, music, musical comedy and putting together multi-media performances that were staged and, alas, disappeared. That seemed kind of a waste, though. "I was sort of longing to put that work into something that could be shown again," said the University of Maryland-Baltimore County graduate, discussing his eventual embrace of film. Nursing an iced tea downtown, seated alongside his son Rob, who was visiting from Philadelphia and has crewed for him, Mugge noted his upbringing wasn't particularly blues infused, though his father did earn his doctorate with a thesis on Black Migration in the South. "I grew up in a civil rights household," he said, but also with family ties to and an appreciation of the culture of the Deep South. He became further taken with it during a stint as Mississippi Public Broadcasting's filmmaker in residence, capturing the history and culture -- including music -- of that state. Later, he was about to accept a job at Delta State University in the Mississippi Delta when Hurricane Katrina brought a watery end to the casinos that were going to fund his position. Tracking down musicians scattered by that horrific storm, however, resulted in his film New Orleans Music in Exile. Other films, which include Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise, have come to fruition in other ways. Channel 4 in England has funded his work. Rock star Dave Stewart of Eurythmics funded and was featured in Deep Blues. What makes Mugge tackle a topic? Adventure. "The adventure of making it is always why you do it," he said. Another reason? "Often the reason is it's something I don't know a lot about," he continued, noting that quest for knowledge has drawn him to make films about reggae, zydeco, gospel music, jazz improvisation and, most recently, Romania. "That was one thing I knew nothing about," he said of the Eastern European country, to which he ventured last spring with a film crew that included Diana Zelman, his fiancée, a filmmaker in her own right who has produced some of his projects. Souvenirs of Bucovina: A Romanian Survival Guide, is currently being edited for release late this year. As the Department of Telecommunication's endowed chair, Mugge spends significant time passing on his knowledge to students who want to follow him into film-making. "I had a feeling if I ran up my flag as a filmmaker ... students would reach out to me, and to a large extent that's happened," he said. He takes great pride in their work. "But I can't stop working on my own stuff," continued Mugge, who also takes pride in never having had to make a film that he did not want to make. "I never stop working." - John Carlson

Robert Mugge's Musical Spirit To filmmaker Robert Mugge, music is a metaphor for the human spirit. “It’s beneath the surface in every film I’ve made,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “Music is a leaping-off place for discussions of social issues, cultural issues, political issues, even religious issues.” Mugge, who will be in town to present three of his music documentaries at the Santa Fe Film Festival, is enmeshed in a project to document the effects of Hurricane Katrina on a city that is a major wellspring of American music. Mugge is making the Katrina movie for the cable network Starz. “The story of what’s happening in New Orleans is so big,” Mugge said, “you can turn on a camera anywhere there and get something interesting. You can talk to anyone you see on the street and get a great story. So music makes it a manageable focus.” Music has been a metaphor for Mugge’s spirit since his early childhood in North Carolina in the early 1950s, when a radio introduced him to the strange and alluring world of American music — country, gospel, and rock ’n’ roll. Mugge began studying film in the early ’70s at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. By the end of the ’70s he’d made documentaries about Frostburg, Md. (an Appalachian mining town where he’d gone to college in the 1960s), and controversial Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo. George Crumb: Voice of The Whale (1976), a portrait of the contemporary avant-garde composer, was Mugge’s first music movie. In 1978 Mugge began filming Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise, a portrait of the Alabama-born jazz spaceman. From then on, music, musicians, and places where music is made have been his focus. Music isn’t shortchanged in Mugge’s movies. Unlike many music documentaries that interrupt great performances for inane fan chatter or irrelevant observations, Mugge frequently allows the whole song to play and let the music speak for itself. And his interview segments almost always go straight to the core. Mugge has made documentaries about bluegrass, reggae, and Hawaiian music and has done films centered on Rubén Blades, Sonny Rollins, Robert Johnson, and Gil Scott-Heron. In 1984’s Gospel According to Al Green, Mugge became the first interviewer to get the soul singer to open up about a terrible night in which a spurned girlfriend threw a pot of boiling grits on him — causing second-degree burns — then went into a bedroom and fatally shot herself. He’s done several movies on the blues, three of which are showing at the film festival. Deep Blues, a 1991 film narrated by Arkansas music writer Robert Palmer, features performances by Mississippi masters R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough — captured on film well before they became cult heroes on Fat Possum records — as well as lesser-known worthies like Jessie Mae Hemphill (both solo and with her fife-and-drum band), Roosevelt “Booba” Barnes, and Big Jack Johnson. Mugge said that a major point of Deep Blues was that pockets of authentic Mississippi blues were alive and well. But by 1999, when he made Hellhounds on My Trail: The Afterlife of Robert Johnson, “I started to sense (Mississippi blues) was beginning to die. A lot of performers were dying, and jukes were closing down.” That concern prompted him in 2003 to make Last of the Mississippi Jukes, which also is showing at the film festival. While it’s full of high-powered performances by Alvin Youngblood Hart, Chris Thomas King, Vasti Jackson, Bobby Rush, and Patrice Moncell, it’s ultimately a sad film. It starts off with a brand-new juke joint in Clarksdale, Miss., the Ground Zero Blues Club, which is co-owned by actor Morgan Freeman. But it ends at the Subway Lounge in Jackson, Miss., shortly before the club closed. At the end of the film there’s hope that the Subway would be renovated and revived. However, due to structural problems, the building has since been demolished. The third film Mugge presents in Santa Fe is Rhythm ’N’ Bayous: A Road Map to Louisiana Music, originally released in 2000. Mugge said the purpose of this film was to show the impressive breadth of music in Louisiana — Cajun, zydeco, Creole, gospel, country, blues, soul, funk, jazz, rock ’n’ roll — and not just focus on “the same people” usually chosen to represent Louisiana music. Among those featured in the movie are jazz trumpeter Kermit Ruffins, rockabilly artist Dale Hawkins, New Orleans rocker Frankie “Sea Cruise” Ford, and blues pianist Henry Butler. Rhythm ’N’ Bayous can be considered a preamble to his new project about Katrina’s effect on New Orleans music, a joyful picture of “before” that will provide a sad contrast with the “after” that Mugge is documenting. In the days before his interview with Pasatiempo, Mugge had been in New Orleans and other locales in the South talking with and filming performances of New Orleans musicians. He found cars on top of houses and in swimming pools, and he saw mysterious men dressed in black patrolling the neighborhoods at night. He filmed in clubs with no running water and unspeakably foul restrooms. Mugge convinced the Army Corps of Engineers to take him up in a helicopter for an aerial perspective of the city and of landmarks such as Fats Domino’s house. Mugge’s co-producer, Diane Zelman, convinced a voodoo priestess to allow the crew to shoot a voodoo ceremony in a neighborhood where electricity hadn’t been restored. At the climax of the ritual — whose purpose was “to bring the city back to life,” Mugge said — the lights suddenly came back on, evoking nervous laughter from all involved. Mugge filmed a gig at Grant Street Music Hall in Lafayette in which Marcia Ball presented fellow pianist Eddie Bo with a new electronic keyboard to replace the one he’d lost in the hurricane. He shot an unknown guitarist playing an unplugged electric guitar on the roof of his mother’s home. “We filmed Irma Thomas going back to her home, which is now gutted,” Mugge said, speaking of the venerated soul singer. “We went with her to her nightclub, the Lion’s Den, which was destroyed. She pointed to these Christmas lights on the wall and said, ‘You guys put those there 12 years ago’” when Mugge filmed Thomas for True Believers, a film about Rounder Records. The new Thomas footage as well as that of Ruffins, whom he tracked down in Houston, will be interspersed with old performance footage “from happier times.” A major question underlying the Katrina project is whether New Orleans will survive as a living, thriving music center. It’s a question Mugge has yet to answer. “Cyril Neville believes there’s a real conspiracy among white financial people to do away with the black, impoverished neighborhoods,” Mugge said. “That’s where the people get this culture that’s responsible for this music.” But even people who are less conspiracy-minded fear that New Orleans will be rebuilt as a Disneyfied version of its former self, perhaps something like Beale Street in Memphis, once a bucket-of-blood crucible of the blues, now an upscale tourist district offering safe, sanitized blues. “People want to make sure that the city (government) doesn’t sell them out and don’t try to turn it into a new Las Vegas,” Mugge said. Many New Orleans musicians have fled and might not return. Ruffins is Houston, Eddie Bo in Lafayette, and Neville in Austin, Texas. “These guys are really good and they’re still New Orleans musicians,” Mugge said. “But if New Orleans ceases to be New Orleans, there’s no place for them. If every city in the country has its own New Orleans musician, are they truly New Orleans musicians if the city’s ceased to function?” New Orleans, Mugge says, “is like a body without a spirit. The music itself is the spirit.” - Stephen W. Terrell, http://steveterrell.blogspot.com/ |

|||||||||||||