|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mouse over the thumbnails above |

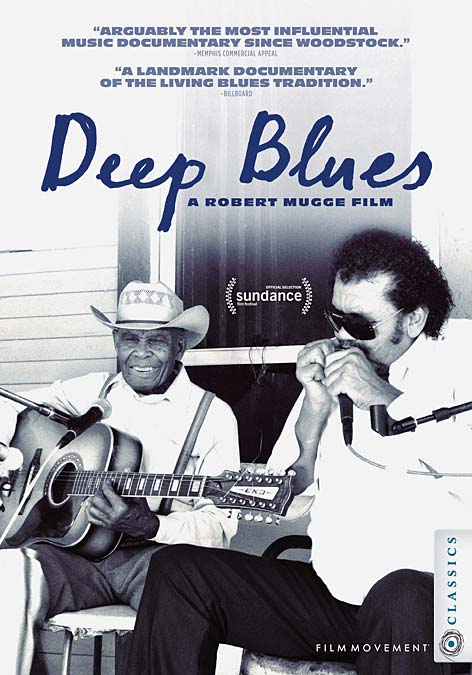

SYNOPSISIn 1990, commissioned by Dave Stewart of Eurythmics, veteran music film director Robert Mugge and renowned music scholar Robert Palmer ventured deep into the heart of the North Mississippi Hill Country and Mississippi Delta to seek out the best rural blues acts currently working. Starting on Beale Street in Memphis, they headed south to the juke joints, lounges, front porches, and parlors of Holly Springs, Greenville, Clarksdale, Bentonia, and Lexington. Along the way, they visited celebrated landmarks and documented talented artists cut off from the mainstream of the recording industry. The resulting film expresses reverence for the rich musical history of the region, spotlighting local performers, soon to be world-renowned, thanks in large part to the film, and demonstrating how the blues continues to thrive in new generations of gifted musicians. FEATURING THE MUSIC OFJunior Kimbrough - R.L. Burnside - Jessie Mae Hemphill - Big Jack Johnson

Robert Mugge with Jack Owens during the filming of Deep Blues. KEEPING TIMEby Robert Mugge In the years after their creation, films take on lives of their own, far beyond what their makers intended. Like children, they grow up, leave home, and engage in relationships their parents could never have imagined, much less controlled. Of the films I’ve directed, none has more clearly demonstrated this principle than Deep Blues, originally completed and released in 1991. Scene for scene, I recall decisions made and actions taken – not only by me, but by executive producer Dave Stewart, producers Eileen Gregory and John Stewart, writer and music director Robert Palmer, line producer Robert Maier, cinematographers Erich Roland and Christopher Li, music recording technicians William Barth and Johnny Rosen, and music mixer Lee Manning – that gave the film its scope, its structure, its rhythms, its textures, and more. And yet, today, I also can watch Deep Blues the way I assume others do: as something separate from all of us; as a window into a world that now exists more as fading memory than as continuing fact (that is, the world of Mississippi blues). Frankly, I consider it a blessing that a film can take on a life of its own because, since we made it, most of the better-known artists who performed for us – R. L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, Jessie Mae Hemphill, Big Jack Johnson, Roosevelt “Booba” Barnes, Jack Owens, Bud Spires, Booker T. Laury, Lonnie Pitchford, Frank Frost, Sam Carr, and Napolean Strickland – have died, as has blues deejay Early “The Soul Man” Wright. So, too, has author, journalist, and musician Robert Palmer, the musical and spiritual guide for our project. As we all know, no one among us can stop the clock, which is one very good reason for having the blues. Yet, every so often, we at least can freeze a moment in time via vinyl, celluloid, or more recent forms of digital audio and video, so that our children’s children can see what we saw, hear what we heard, know what we knew, and maybe even feel what we felt, regarding great American artists, whether widely known or not. In that respect, the moments we captured in Deep Blues are very special indeed, which is why the film itself lives on, even as so many who worked on it, or appeared in it, are slipping away. That the film exists at all is thanks entirely to the generosity of executive producer Dave Stewart, who paid for this project out of his own pocket, declaring that he wished to “give something back” to traditional blues artists who had inspired him when he was starting out, and who have continued to inspire him ever since. Moreover, on this, the thirtieth anniversary of the film’s release, he has underwritten its remastering in 4K video so that our new distributor, Film Movement, can “relaunch it” in accordance with current distribution standards. On such an occasion, perhaps I should clear up two longtime misconceptions. First, from the beginning, executive producer Dave Stewart and producer Eileen Gregory intended Deep Blues to be a film, which they hired me to direct and edit, and Bob Palmer to write and narrate. The notion that Bob was hired to record audio of Mississippi blues and then produce a CD was simply a narrative device I devised in order to tie together widely disparate scenes my crew and I were preparing to shoot and record, and the CD Bob eventually did produce was merely an after-the-fact soundtrack album derived from the crew’s recordings, though a a great one, of which Bob and Dave could be proud. Second, the film was never intended to be called Deep Blues. That came about late in the project, because the producers and I could not agree on a title. Facing a deadline for completion, I asked Bob if he would permit us to borrow the name of his 1981 book, and happily, he agreed. Of course, this also represented a logical compromise, because the film, like Bob’s book before it, does reflect his underlying belief that African-American musicians of the Deep South, drawing upon their unique history and cultural heritage, produced the deepest blues ever created, which was true of those who remained in Mississippi, just as it was of those who migrated to Memphis, Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Kansas City, and elsewhere. In conclusion, origin stories aside, please know that we, as proud parents of this newly remastered film, are pleased to share, still again, some exceptionally deep and varied blues, and hope to continue doing so for many years to come. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Click On the Images Below for a Larger View | ||

|

INTERVIEWS ABOUT DEEP BLUES Ned Sublette, host of Postmambo Movie Nights, interviews Robert Mugge about his 1991 film DEEP BLUES Conducted via Zoom on May 19, 2022. Recorded January 26, 2022 and first available on January 29, 2022. (Audio Only) Recorded January 19, 2022 First available online October 18, 2021. (Audio Only) Knut Benzner of Germany’s NDR radio interviews Robert Mugge about his 1991 film DEEP BLUES Broadcast April 13, 2020. (Audio Only) Broadcast December 15, 1992. (Audio Only) Derek McGinty of WAMU-FM interviews Robert Mugge about his 1991 film DEEP BLUES Broadcast September 30, 1992. (Audio Only) Bob Porter of WBGO-FM interviews Robert Mugge about his 1991 film DEEP BLUES Broadcast July 31, 1992. (Audio Only) Mark Scheerer of CNN interviews Robert Mugge and Dave Stewart about their 1991 film DEEP BLUES Broadcast January 22, 1992.

|

||